| INSTA WORKS TEXTS CONTACT |

| ESSAYS CATALOGS EDITORIAL BIO+ |

| JAIME PRADES |

|

||||

|

|||||

|

||||

| DIÁFANO ART MAGAZINE 2019 DB/ARTEFACTO 2018 CASA & CONSTRUÇÃO 2018 BRASIL FAZ DESIGN 2017 CHAPEL ART COLLECTION 2017 ENTREOLHARES 2016 THE ART OF RECYCLE 2015 REVISTA BRASILEIRA 84 2015 GRÁFICA INTERNACIONAL 2014 PANAMERICANA 50 ANOS 2013 PINACOTECA DO ESTADO SP 2013 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC BRA 2013 ESTÉTICA MARGINAL 2012 MAC PARANÁ ACERVO 2009 THE ART OF JAIME PRADES 2009 TUPIGRAFIA 11 2008 ARTE EM SÃO PAULO Nº 31 1985 |

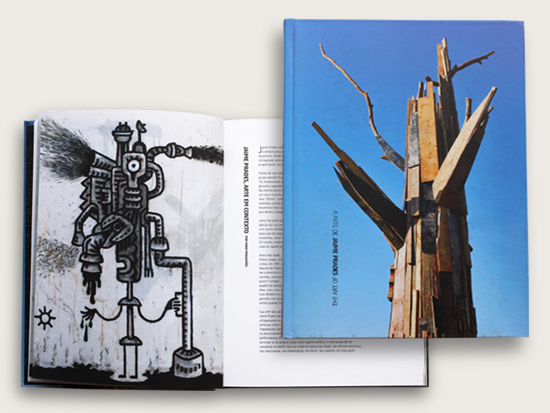

THE ART OF JAIME PRADES 2009

Fabio Magalhães - Editora Olhares/2009.

26,5 x 20 x 2,6 cm, 158 images, 252 pages, text in English and Portuguese. JAIME PRADES, ART IN CONTEXT From a tender age, Jaime Prades adopted experimentation as a creative attitude, always striving to diversify his means of expression, which are not limited to painting. His projects crossed the barriers ordained by modernity, and since the ‘80s his restlessness has driven him to pursue untraveled paths, pointing to new horizons. Many of his innovative ideas were shared by German group Fluxus (flux is the Latin word for catharsis), which revolutionized the concept of art in the 1960s and 1970s, deeply influencing later generations. The work of Joseph Beuys causes immense impact even today. It is worth noting that at the same time the Fluxus group was stirring the European artistic scene, a new concept of art was also being developed in Brazil. Lygia Clark and her “Bichos” (“Beasts”), and Helio Oiticica and his “Parangolés” are just two examples of artists who brought about irreversible changes to the Brazilian artistic production, and who are today internationally renowned for their great contribution to world vanguard. Jaime is part of the ‘80s generation. Nevertheless, he was one of the pioneers in using the streets as the space and the support for his work. Along with other artists of his generation, he established new concepts of artistic language for public spaces. Other wandering artists such as Alex Vallauri and Mauricio Villaça appeared a while earlier, and still others came later, including Zé Carratu, Hudinilson Junior, Rafael França and many more, who would roam the streets of São Paulo. Years later, Jaime Prades made the following declaration: “on my way home, looking through the window of a crowded bus, carrying my stuff and 23 years of age on my back, I saw, in 1981, for the first time, a graffito by Alex Vallauri. I don’t mean the letterings and writings that were always there and, I assume, will always be. I mean very graphic drawings: a pirouetting acrobat, almost a stamp; a sexy boot; a phone stenciled on the wall... to talk to whom? To me?... Years later I found out that this acrobat is a detail from a Georges Seurat painting, "The circus", from 1891, now in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. Alex, with the erudite view of an engraver, went beyond reinterpreting it, taking this detail and stenciling it throughout São Paulo and Nova York”. This quote alone allows us to make associations and recognize the artist’s poetic and conscientious attitude when he went out to the streets”. His art did not fit inside a studio. And his studio was no longer the same. Jaime Prades would work in any space. In order to carry out their projects, many other artists from this period crossed over the geography of the plastic arts, breaking into other forms of artistic communication, such as the theater, cinema, and literature. They used new materials, including garbage and perishables, to develop their proposals. They expressed themselves through happenings, performances, installations, video art, and various other media, also using the body as a support for their art. The work might be conceived in the studio, but it was created in areas of the city: garages, joineries, workshops, alleys, viaducts, everywhere. Jaime moved between the studio and the streets. We should note that street art started in Brazil in the ‘70s and remained excluded, outcast. City legislations throughout the world fight graffiti, and street art is therefore transgressive in its very nature, and defying the established order is part of its very essence. . Creating street art imposed to the artists a somehow clandestine attitude; execution needed to be stealthy to avoid arrest, to stay away from the police. In order to face this risk, street artists developed quick techniques to record their images and concepts, such as stenciling or stamping, both used by Alex Vallauri, as well as chalk, used by the Tupinãodá group. When an intervention required a longer time for execution, as was the case with large murals and urban installations, the solution was to form crews or to adopt means of collective work. So the street artists would take turns in working and watching, and thus imposed a new dynamic to the implementation of their projects. Art collectives first appeared in this context. The first street art collective in Brazil, of which Jaime Prades was part, was known as Tupinãodá. The name was taken from a poem by Antonio Robert de Moraes: "Are you Tupi from here Or Tupi from there, Are you Tupiniquim or Tupinãodá?" During the dictatorship the group created several socially critical installations. These were difficult times, but still the artists strived to break the restrictions and the authoritarian power, through transgressions and manifestations in urban spaces. In 1984, Tupinãodá created an installation using garbage bags on the gardens around the Architecture and Urbanism School, in the state university campus. Jaime Prades later said: “The planet is not a garbage can, but its wealth is garbage!” Afterward, the group fashioned huge letterings in chalk. Such urban interventions would take us by surprise, ephemeral presence on walls that would disappear a few days later, erased by the rain and the wind. The members of the Tupinãodá group were conceptual artists that produced graffiti, installations and performances in public areas. Jaime Prades does not consider himself a graffiti artist, nor a street artist; his work as an artist is much more comprehensive. However, the power of his large murals, painted on concrete in areas of high urban visibility, revealed Jaime Prades to the great public. The “Machines”, a massive mural that covered, for years, one of the walls of the Paulista Avenue tunnel, caused such an impact that shadowed other works, and Jaime Prades consequently became known as a street artist, linked to the world of graffiti. My first contact with Jaime Prades happened towards the end of the ‘80s, and as many other art critics I was also interested in his street pieces, in the “Machines” series. The “Machines” were a combination of robotics and wildlife, a symbiosis of rockets and feral animals. They were built by putting together an infinity of small parts, which once articulated formed sets of great vitality and of an extraordinarily explosive potential. The small parts were painted red, white and black, resembling the work of Jean Dubuffet, as noted by art collector João Sattamini, at that time the owner of one of the most prominent contemporary art galleries in Brazil. From then on I followed the work Jaime Prades was developing in his atelier, as well as the installations and interventions he had already created. I was attracted to his carvings on wood, a variation of the “Machines” project, idealized for the walls of the city, and to the objects of the “Bastards” series, made from discarded wood. The artist collected construction debris and pieces of furniture from the streets, which he would then treat and paint, taking care not to conceal their original intent (door, window, fragment). At the same time he came up with the “Verticals” series, using new materials such as cement and iron, among others. The fertility of this imagination and the strength of this poetry were closely related to the anguishes and challenges we were forced to face in our daily lives. They were marked by our times, calling our social and environmental blunders to attention. They spoke of the place where we lived, denouncing the absurdity of our quotidian existence, without losing view of hope and pointing to utopias. Jaime built a powerful language at the margins of galleries, exhibitions and museums. The artist and his crew occupied the city’s spaces, consecrating them through the introduction of art, and profaning the art by introducing it on the walls and edges of the city. In the early 1990s, I was director of MASP, the São Paulo Museum of Art, and I invited Jaime Prades to show some large pieces of his “Absurdities” series in the museum. Today I see his huge sculptures – “Human Nature”. They are dramatic, touching works of art. Jaime rebuilds a tree from planks and nails. He creates a metaphor of the natural life with pieces of wood, construction debris. The plank is, in itself, the corpse of a tree, and the plank, as construction waste, represents a superlative death, a step ahead in the eschatology of all things. Jaime uses this blatantly dead element to reconstruct the tree “nature”. The result is surprising. The “Human Nature” work questions the perverse links of our relationship with the environment. However, the poetic possibilities of the work go beyond the ecological discourse to make us reflect on the voracity of life in our society. Fabio Magalhães On the afternoon of September 25, 2009, in Jaime Prades’s studio, in the district of Sumaré, São Paulo, we talked over his work and his artistic trajectory. Fabio Magalhães: I would like you to tell us about your education, about how you entered the arts, about how it all started. Jaime Prades: In order to do that, I need to tell you some of the story of my life. My mother is Brazilian and my father Uruguayan, and I was born in Spain. I am Brazilian, and I was born in Spain. My father was a filmmaker, and he was in Spain making movies. I spent my childhood surrounded by artists of various types, from scenographers to plastic artists, of all schools, people whose common link was a militant work, fighting against the Franco reality. They made a picassoesque cubism, more picassoesque than Picasso himself; a defiant attitude… I grew up in the middle of that. Javier Clavo (1), a Spanish painter who was a friend of ours, made a portrait of me aged four. I was always in the ateliers. FM: Where in Spain? JP: In the south. I was born in Madrid, but my father had a condominium near Marbella, Cortijo Blanco, in San Pedro de Alcantara, between Malaga and Gibraltar. Many artists had their studios there. It was quite different from what it is today, 40 years later. It was a much more private area back then. And we would spend three or four months a year in this place… Until I was 11 years old, my life was kind of like that. We came to Brazil because my father was very ill and going through serious financial problems. The moving had a great impact on my life. It was a moment of immense loneliness. That is why I started to draw. And in the drawing I found an inner space, this haven that is art. That is why I am so fond of handiwork, of the work of amateur painters. I always take notice of it, because I lived that in my own life and realized that art has a curative role, it is a sanctuary. In art you can find silence, tranquility. Art had this role in my life, it happened naturally. And my challenge during all this time has been to, somehow, keep this connection. FM: Always self-taught? JP: Always self-taught. But I did take several courses. The first was during the Ouro Preto Winter Festival, in 1973. They had these live models. I had never drawn from a model before, and ended up in a model course and it was quite remarkable. I started drawing, and the people taking part in the course would look at my drawings and say, wow!… And I had no idea of what that is worth. I had contact with some amazing artists during this festival, including Álvaro Apocalypse (2). FM: Yes, a great artist, who had an important role as a teacher. JP: He mastered a fantastic technique. I remember one day in Ouro Preto when I was watching him drawing, and he said: you should keep up your work, keep on drawing, keep on going. I was a kid, 15 years-old. Seeing Álvaro Apocalypse drawing was amazing. And I had already seen great draftsmen working in Spain. The one that left the deepest impression on me was Antonio Mingote, a cartoonist whose drawings were wonderful. I personally believe that art has, in a way, been like a bridge in my life. Because there were so many fractures, interruptions during childhood: family, country, friends, economical conditions… And I can weave my story because art has, in a way, kept my childhood alive, kept my story alive, created my identity. So much so, that I continue to make art in this self-taught way. Learning from my experience, from my living. I took a xylography course, and a live model course, and later I took a course on metal engraving when I came to São Paulo, in 1975, with José Guyer Salles and Selma Daffré. My attention was on the arts; that was the only thing I was sure I wanted to do. After working for a year as a carpenter assistant, I got a job at Editora Abril, a major publishing company in Brazil. I ended up there because of my drawings, and that is how I got to know the publishing business, the graphic arts, all of that stuff, way before computers came up. I had quit regular school, and at night I was taking a course at Escola Contemporânea de Arte, a school outside the art circuit. But that was where I met Rubem Valentim (3). He was a friend of the owners. His work is of archetypal constructivism, with a very powerful formal austerity. I also went to Pinacoteca do Estado, a major museum in São Paulo, every Thursday evening to take a live model course with Gregório Gruber. FM: When did you professional life as an artist begin? JP: I had my first exhibition at Escola Contemporânea de Arte, and Rubem Valentim was there to judge the work. My drawings were realist, an expressive work with models. I picked drawings that were very sad. At that time, I had been reading the letters Van Gogh wrote to his brother, and those Van Gogh charcoal drawings populated my head. Influenced by that, I had made these very dense works, a series of drawings of my then girlfriend. I still have those drawings. This was my first exhibition, and something was published in a major newspaper, Folha de São Paulo, but I had no idea of what that meant. At that time, my father was very ill, we were going through a complicated phase, I was 18-19 years-old and was not aware of a lot of things. So much so, that I did not have a project for my life, nor did I have a goal, as in: I will study this to do that, etc. FM: What was the importance of Editora Abril to you? JP: It was very important. First because I got to work in a company, and second because I learned how to do all this publishing stuff, it was my introduction to the industrial graphic arts, which is something I still use in my work today. It was the time of the military regime, and in our generation you could not remain neutral. Our generation was militant, we took that to heart, and later it lead to Tupinãodá. But when I left Editora Abril I went to Oboré, another publishing company. I went to work there because I was a fan of cartoonist Laerte. I worked with him for four years. We did Lula’s union newspapers, periphery stuff… At that time I was completely immersed in political activism. After I left Oboré, I met Zé Carratu, who was one of the mentors of the Tupinãodá group. He asked me whether I would like to share an atelier with him, a studio at Rua Cardeal Arcoverde. I worked in this studio hectically for two years, catching up on lost time. It was a phase of intense experimentation and study of drawing and painting techniques. I joined Tupinãodá six months after it was founded. The first crew was made up of Milton Sogabe, Eduardo Duar and Zé Carratu. Then César Teixeira and I joined. Two geographers from USP (the São Paulo state university), Armando Correia, who passed away, and Antonio Robert de Moraes, known as Tunico, also played important roles in the creation of the group. Actually, Tupinãodá came before graffiti. There was, of course, Alex Vallauri, but at that time no one talked about graffiti, it was something not fully labeled, that was not in the media, still in gestation. FM: What about Carlos Matuck, was he not a part of it? JP: No, he worked with Valdemar Zaidler. They were first inspired and stimulated by Alex. They were from another nucleus, prior to Tupinãodá; we could say they were of the stencil school. They took stenciling to an amazing height, refining it to a point where they ended up influencing even Alex. FM: And what about you, did you also work with stencil? JP: I only did one, at that time, a reproduction of a Tarsila do Amaral sketch for “A Negra” [The Negress]. We were very interested in the Antropofagia movement, in Flávio de Carvalho, we felt like we belonged to this family, we identified with them. The great contribution of these artists was that they laid the foundations for us, just like we did to other generations. The cultural life is like that. FM: And what about the playful reference to Oswald de Andrade of this name, Tupinãodá? JP: Exactly, the name expresses that playfulness. It was taken from a poem by this geographer, Antonio Robert de Moraes: Voce é tupi daqui ou tupi de lá, é tupiniquim ou tupinãodá? FM: Beautiful poem! JP: It is certainly not beautiful! And Zé grasped the idea: Tupinãodá is a word that is a paradox, something odd. Zé is good at grasping stuff, at performances. He was the one to bring this energy to the group. Armando was Tunico’s supervisor, and a geographer who left a legacy of thoughts on space that are very valuable to Brazil. He wrote and published articles on the space of mind, as a geographer. That encounter of artists and intellectuals originated the group and the concept of urban space as a stage and as a support. In fact, graffiti was never the motivation. Our first works were public installations. For MAC [the Museum of Contemporary Art], we created a billboard to which we tied three huge garbage bags, each a color of the Brazilian flag. Then we made another installation, also using garbage bags of the colors of the flag, on a grassed area at FAU [the Architecture and Urbanism School] in the USP [University of São Paulo] campus. For the first graphic interventions we made on city walls we used chalk on black-painted backgrounds. Then we started using paint and rolls to make larger works, because we wanted as much impact as possible. We were right in the middle of the transition from a dictatorship to a democracy. What I think is that when the pressure cooker started to open, paint gushed out. We were already on the streets trying to make these massive interventions, and we were working during daytime, our goal was to take over this space. The political situation was still very tense. Going out on the streets was a dangerous thing to do… it still is today, right? The streets are always dangerous, but back then the danger was veiled. And the most incendiary element was that our discourse was completely playful in terms of the imaginary. But going out there to do that, exposing oneself, that was what was indeed political about it. FM: The streets back then were different from the street art today... JP: Before Tupinãodá there were only the stencils, which was what freed everyone’s mind… Alex Vallauri. It is important to remember that this story was not told, as it should have been. He was contemporaneous with Keith Haring and Basquiat, in New York. He went there and did graffiti in New York at that same time; I even think they all knew each other. Alex first worked with engravings. Then he started to do stencils, a technique that has similarities with engraving and is compatible with the graphic printing processes. FM: When was Tupinãodá born? JP: It was born in ‘83. I left in the end of ‘89, and the group continued until ‘91. There are a series of works that Zé Carratü, Carlos Delfino and Ciro Cozzolino made after I left that are worth mentioning. They would copy landscapes from popular paintings – those classic scenes of a little countryside house by the river in flashy colors – and would then make crazy interferences on that base. They did a genial work at the MAC [Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo] gate in the Ibirapuera Park, that created a huge controversy, because the museum director thought it was hideous and had it erased. What is amazing is that ten years later, Bansky did almost the same thing in England, and he is worshiped. Now, back to ‘87, which was when Trama do Gosto (The Web of Taste) took place – a preparatory event for the 24th Biennale. It was really great, Leonor Amarante wrote a text, curatored by Maurício Vilaça and Alex Vallauri, who was very ill and died not much later. They put together all that was there in street art, and that gave us a lot of strength. FM: And the Biennale brought Keith Haring and some European graffiti artists… at what spots of the city did you do your interferences? JP: A lot at Vila Madalena, but we also did some stuff near the Pinacoteca museum. In ‘86, Pinacoteca had a curatorship project that was called Contemporâneos, and they invited us to participate. We had never had a show anywhere before. It was the first time we did something institutional, the first Tupinãodá exhibition. Rui Amaral, Zé Carratu and I. We took some large wooden shipping crates, and painted everything inside and out. At that time the Pinacoteca had a central arena, and we drew everywhere using chalk. It was quite a radical installation. That was early in ‘86. Maria Cecília França Lourenço, the museum director, wrote the text, and that was our first portfolio/catalogue. At that time, my work was still undefined, but the issue of the line, of the drawing, was always predominant. I see myself much more as an artist of drawings, of lines. Painting comes in as a complement, I see myself as a draftsman. FM: How do you see the difference between the studio and the street? JP: The very process of making this book made some things clearer to me. It is like a braid, a single thing – the street contaminates the studio, the studio contaminates the street, and I find solutions in one space and carry them to the other. I see it as a sort of breathing, a mutual process of inspirations. FM: Have you kept a permanent relationship with the streets? JP: I did not work on the streets for many years. Starting in ‘91, all of my generation stopped working on the streets; that was when the tag wave came from the south side, from the Santo Amaro district… I think you remember it, the beginning, it was like fungi covering everything, including our drawings. And on the side was Jânio Quadros, at the time mayor of the city of São Paulo, who had a conservative and authoritarian attitude and tried to appeal to the artists. Street art was not my only line of work. I never took part in the actions organized by the City; that seemed incongruous to me. FM: Was there a street ethic in the relationship with the graffiti gangs and writer crews? JP: There never was. I see it as more of a social-economical issue... FM: Don’t writers respect graffiti art? I believe they do nowadays. Writers have developed occupation ethics. JP: There was a huge problem during the last Biennale… FM: That is a different matter. They occupied an area left empty... JP: You are aware that the pixo is there, in the Fondation Cartier in Paris, right? FM: Yes. It is part of the everyday life of the cities. JP: We are living an interesting moment. FM: I don’t mean to change the course of the interview, but I do believe there is an ethical relationship on the streets. In order to face the dangers of the street, the artists must be, so to speak, clandestine, or at least a painter who does not respect certain rules. When you interfere on walls, bridges, viaducts, you are going against the norms. So you need protection, you need a partner and the complicity of the group. The same that happens with street vendors, where they defend each other, warning each other when the police is coming. Another aspect I notice in street art is its collective nature. Large murals are made collectively, where each artist works in certain areas of the wall, even if the crew almost always attempts to create an ensemble, to build a whole. And this whole does not suppress the individuality of each artist. So I see ethics and solidarity in street art. I also think the attitude of the pixador [writer] has changed a lot. Nowadays the pixador cares enough to create an alphabet, there is some level of formality; we could call it a search for identity disguised as anonymity. And also, the pixador today has moved on to other paths, urban adventures, such as climbing to dangerous spots to put their signature on a place to which no one has access. So I see that the street has a life of its own and, for that exact reason, requires specific behaviors. What has been interesting me lately in street art is the fact that the street is a boundless, open field for the dialogue between different social groups, or, if you like, for the confrontation with the city. Street art follows other paths; it does not occupy the same spaces as galleries, the mainstream spaces of contemporary art. I see contemporary art as very rich, creative, but turned more and more to itself and to the market, while street art keeps an element of freedom. My opinion on street art changed a lot in the last years. I used to see nothing but aggression, but today I believe that street art revitalizes urban spaces, its shows great love for the city, which is, evidently, another type of love, different from the one established by urban rules. Graffiti artists wish to interfere in buildings, squares. The graffiti takes over a space and leaves its mark, its imprint. While the small bourgeoisie drives cars and sees the city through glasses, afraid of being contaminated by the outdoor spaces, in fear of intimacy with the mobs. The street artist, on the other hand, lives the city intensely and works in its guts, in the darkest alleys, showing these guts to those driving through the avenues, locked in their cars. And that displeases the middle class, the elites. JP: It is amazing that you should say that, particularly this image of the car glass, because I have been thinking a lot about the issue of aesthetic values. For example, in relation to the arts: what is valued today, what people think is good. It is somehow always filtered by some kind of glass. People are always placing a gelatinous matter – something that makes them feel protected – between themselves and the world: some type of capsule or power field. It can be a computer, a car glass or a digital photo that is there, picturing the reality, but taking something tridimensional and turning it into 2D. I see that in my work – the trees –, the fact that I am making the frames out of charcoal, which is wood. We are somehow distant, alienated, from what is real, just like our civilization today is alienated from nature and from things as they really are. So I feel very close to what you said, because I think that way. I practice walking, I walk everyday. And street art is an art of walkers, because only by walking can you find these places. Then you really see the situation, because you see the garbage, the deteriorated areas and you meet people, old people, children, living among the garbage. Then you forge a true bond with the city and move toward what people do not see, or wish to hide. FM: Back to the studio: when did you first start with the carving? JP: Do you remember João Satamini, from the Subdistrito gallery? One day I was in the atelier, in Vila Madalena, and the phone rang; he wanted to talk to me. Subdistrito was the most important gallery at that time, with the most transgressive aura, the most provocative. And he proposed doing a solo exhibition, he said he had loved my ships on the streets, said that it reminded him a lot of Jean Dubuffet. Although I knew a lot of artists, I did not know Dubuffet’s work; it was Satamini who called my attention to him, and I then checked who he was. But I was very committed to the group. Today we are known as the first public art collective, I don’t know if in Brazil, but in this post-dictatorship transition process. There are loads of collectives today. FM: Yes, now it is widespread, which I find very positive. Collective work is always enriching. JP: Back then it was just us. And I negotiated a collective exhibition with Satamini. We used wood and other wastes as supports, which we painted, reproducing the same imaginary world we created on the streets. But that was the first time I dealt with this conflict, which is the most complicated, I think, for anyone working on the streets: creating something and trying to find a support that brings the power of the street. It is almost impossible. It is a dilemma, because you come to this place that is full of history, of signs, of time, of memory, of humanity, of dirt, of traces, and you make graffiti and it looks amazing. But you can’t just take a piece of wood and try to make the same thing outside of this context. For 20 years I have been trying to find solutions, and I am still trying, because when you do a work in the streets, the result is quite striking. First because you have access to huge scales. After that, doing a 6’x 6’ canvas in studio is nothing. How do you solve this in other supports? How do you hang on to this power that your work acquires in the street, to the relationship you have with the architecture and with the signs that are alive in the city? This is the dilemma: how to transform graffiti that has public dimensions and belongs to the city into private work. My first carvings, which I created for the Subdistrito exhibition in 1987, were born from this struggle, from this contradiction, from this problem. FM: Then in ‘93 you made this series of absurdities, which was shown in MASP when I was directing the museum. JP: We had this idea, which was also born from group discussions, of making a type of art that was accessible, a supermarket art. We thought about it, Carlos Delfino, Zé, and our friends from the Xarandu Group: Vera Barros, Carlos Barmack, Marta Oliveira and Eduardo Verenguel. These were artists that thought in that line. We were anticipating what was already happening in the US. We wanted to make an art that came in another format, an informal art, a pocket art. Incidentally, the street was also not only a political issue in relation to the general politics of society. It was also political in terms of the art system. There was no space for us in the mainstream, so we took another space. There were these two primary issues: criticizing the conjuncture, and also a vital need to show what we were doing to face a system that turned it back on us. We found a way, and I think that will always happen, this tension will always bring about solutions that cause things to evolve. FM: Also, on the other hand, the nature of art changed in contemporary times. After the ’70s, art abandoned the traditional supports. We can say that, somehow, the studio concept changed radically, which broke the barriers between the studio and the street. When happenings, installations or some movements such as Arte Cidade started, they slowly destroyed this notion of the sacred places of art, such as the galleries and museums, and the profane places, such as the streets, creating a relationship with no boundaries. JP: Just to give you an idea: we saw Arte Cidade as an approach, but it was something that could not get close to us. FM: The gallery artists wished to come closer to this space, but did not want to make room for the street artists, who, actually already owned the city. It was an invasion of the studio into the urban spaces, a sort of “biennale of the street”. JP: That is it, and people made amazing, very important stuff, but there was no encounter between us. FM: How have you been surviving from art? And how do you relate to the market? JP: In spite of the permanent conflict of how to survive from art, to have material success and be able to dedicate exclusively to creating, for me there was always something more than just wishing to sell my work. An essential relationship with art making. My work is not at the service of the market. Today, I see it clearly that my art is at the service of conscience and evolution. In order to survive from art, my strategy was to diversify my activities, with different types of work linked to creation for a more commercial market, such as art direction and graphic design. For instance: for the past five years I have been creating the ambience of all new Playland shops for the Playcenter group, using my characters. It is a massive project that we have been developing over time, and I am very pleased to think that this more playful creative side of my art reaches now 5 million children per year. In the future, we dream of making together theme parks for kids. .In parallel, since 1991 I have been creating and producing, in my studio, thousands of sculptures of the Absurdities, pieces with an informal concept of accessible art, a type of anticipation of the designer toy craze. In addition to generating an income, they were also important in divulging my name, and ended up all over the world. I am now launching the new series of pacifier carvings in black and white, with an amazing technical resolution, which I will sell on my website. In terms of the art market, I sold some of my work directly even before my first experience with João Sattamini in 1987. I sold some work through marchand Mônica Filgueiras, many years ago. Also, between 1996 and 2002 I had a fairly active relationship with collector and marchand Martin Wurzmann. All here in São Paulo. Through Martin, a lot of my work ended up in major private collections, mostly in São Paulo, but also in Europe (France, Italy, Germany and Spain) and in the US, as far as I know. The truth is that most of my studio work was spread out in private collections without ever being shown. An important role of this book will be showing this body of work. During the period of this partnership, I lived for some years exclusively from the sale of works of art. In 2002, I recovered a wider range of activities in order to repossess total independence in the direction of my production. I have also been doing more and more indoor graffiti in houses and apartments. And I continue to sell my canvases and sculptures, developing my projects and participating in projects others propose to me. FM: But back to the carvings… JP: Yes, then I started working with that, I did a show at Masp, which was very vital… it was all very vital. I am using this term because that is what it was, this was what I had to say, they were questions of life or death, that was the meaning of my life. FM: And that was a time when Masp was a reference, was really the center of cultural activity. It was an important moment, with a lot happening at the museum… But with these carvings you deal with new issues, you become independent from the walls, you enter the 3D world without giving up the 2D graphic art language, right? You start to enter the world of objects and architecture. And this issue of objects and architecture, is it something that will remain in your work? JP: Yes, these carvings are always present and evolving. If you think, for instance, of what happened with the designer toys, did you follow that? It became a phenomenon… FM: But not very expressive in Brazil. JP: Yes, because it is expensive. FM: It is expensive, and it requires a lot of technology. JP: It is really quite difficult to do, because it must be made in china, you must bring a container, a few thousand… I had an experience with Playland recently when we made 35 thousand dolls. A lot of people have come to me and said – you were doing designer toys in the early ‘90s. I didn’t know it, but there is a connection; this format worked as a concept, but in commercial terms it was too expensive. Still, it is part of my work. FM: So you made use of your carpentry experience? JP: A lot. And I have always researched, always tried to develop technology. I used the first laser machines when they arrived in Brazil, I was one of the first to use MDF when it was imported from Chile. I was always very up-to-date when it came to materials and techniques. Self teaching means studying all the time. When you take a course at a university, you study, and, of course, you can continue studying, but I have always considered each piece as a diploma of my permanent research. And at the cost of total risk, as with any artist. FM: And when did you start using computers? JP: Quite late, in 1995, ‘96. FM: But it slowly became a language that you are quite familiar with, right? Especially for the type of graphic work you do, 3D without loosing its graphic features. I note computers are an important tool in your work. JP: It is am amazing tool. It provided new resources in the field of images. Publicity first made it viable, introducing these new tools here in Brazil. FM: Something else: you work with a mixture of figuration and abstraction, organic and geometric, I would like you to talk a little about that. JP: I slowly came to understand that I work with signs. And the sign is exactly the visual element that has features both of abstraction and figuration, capable of uniting these two opposites that are apparently impossible to conciliate. I see myself as an inventor of signs. A sign is a manifestation. If we take, for example, the hermetic tradition of ancient Egypt… FM: Or Spain, which is part of your life story. There are important Spanish artists such as Miró, Tàpies, Brossa, Chilita, all of which work with signs and retrieve a lot from this ancestral world of Hispanic signs. There are texts of Tàpies and Chilita. Another important figure that I would like to mention is Torres-García, whose works link the Latin-American to the Hispanic world. At certain points, I see a strong connection between Torres-García’s and your work, much more than with that of Dubuffet. I have also been assiduously observing your artistic trajectory since the Tupinãodá period, and I would also include two other artists as your blood relatives: Rubem Valentim (3), who works with African signs and geometry; and Ronaldo Rego (4), an artist linked to the rites and expressions of African religiosity. Ronaldo is from Bahia, as is Rubem Valentim, and not very well known, although he participated in the anthological Magiciens de la Terre exhibition, in 1989, at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Both produced works that are closely related to yours. FM: How do you see this relationship between geometry and sign, this construction of geometry based exactly on a very ancestral memory of signs that take part in the very creation of myths? JP: I will try to explain my process of understanding of my own work. First, I should say that, for me, being related to Torres-García is a joy, because I think he is a giant who literally inverted the continent. And I did not know his work, until, once again, someone else said: see, this here looks like Torres-García. And then I did some research – like what happened with Satamini and Dubuffet – and I was captivated by his work, by his philosophy, by his life, by his significance. This is how it happened to me: I went to the street and I made those machines. They were an attempt at translating an extremely aggressive urban reality into images. To me, that is aggressive. Today, coincidentally, I am going back to making machine-beings. I am using the machines because I want to show things that are highly aggressive, especially to the environment… I want to create signs that address this issue of what is happening to the planet, and of how we are collectively behaving in relation to that. FM: That is where this world of yours of discarded objects comes from, the intervention in the dumpster. These are more recent, right? JP: Yes, they are more recent. In 2007, I went back to the streets and started again to collect discarded, abandoned objects. FM: And what about the machines? JP: These machines, this disorder that creates a possibility of intimacy and unfolding, for me this was also a way to resolve the art in the situation of the real life, there on the streets. A way to create something huge that could be unfolded and had a great graphic effect. I found that, that happened to me. That is the amazing part! The streets put you in these situations; experimenting this type of thing is like an initiation. Dubuffet gave me a resource: he talks about conscience flow. And when I read that, I thought that was exactly what I was experiencing. It is something similar to what I found, for instance, in meditation. It is like a feeling of channelizing something. It is spontaneous. I think graffiti has this role of stirring the contemporary arts. The spontaneity of being an artist, of being there, of really enjoying existing, the being there itself, instead of trying to control everything. As if that was possible. The graffiti brings back the lack of control, in a controlled manner, of course. It is like surfing, it is quite similar to a radical sport. And it actually is; you have adrenalin on the streets. So when I got Dubuffet’s concept of conscience flow, I understood I had a key there. For instance, if I look at Keith Haring’s work without knowing who Dubuffet is, I see it one way; but if I know Dubuffet, I will interpret it in another completely different way. FM: And he opened the path to the understanding of another means of expression that he called art brut. JP: Exactly, and he somehow recovered the sacred right there. I believe that the modernism and the movements from the turn of the 20th century, in particular the more combative artists, such as Picasso, had a leap because they incorporated Africa. That is my intuition: that Africa saved Europe. Art evolved because it recovered the sacred, the ancestral. And when Dubuffet calls our attention to art brut, I think that he discovers the sacred right there, not all the way in Africa. And that is another place where I go, this idea of art made with simplicity… Calder also does that; if you look at Calder’s face… he is like a child. FM: A huge child. JP: He has that, a brut artist, in the sense of making art of extreme purity, but at the same time having considerable background, it is wonderful! Those are my references. FM: To wrap it up, I would like you to talk about your last work, “Human Nature”, this reconstruction of the tree, which is intelligent and disturbing, because you discuss the issue of life. The plank that remakes the tree is, in itself, a contradiction of great poetical power – the construction of a life metaphor from elements that symbolize death. JP: We were molded by that process of the end of the dictatorship; we lived that transition and went out to the streets to express ourselves. We made political art with no proselytism, and political in the polis sense of creating an art that was really directed to the collective, to the society. Now, 20 years later, we live a conjuncture that is no longer of our country, but planetary, and which indicates a new transition; something has got to happen. We are on the verge of a leap forward and on the verge of a leap backwards. The current situation calls to all of the planet’s intelligences to do something to stop destruction and, as an artist, I feel it is my duty to find a way to say this to people. This return to the streets is part of this, of this urgency. And it was on the street, while looking at a piece of wood thrown away in the garbage, that I saw this image of its origin as a seed that budded miraculously in the forest, became a tree, was cut down, used and discarded. By seeing this cycle I realized how a forest falls down every day in the cities. The Human Nature project consists of building trees, forests, from these wastes. I want to make them in major cities of the world. FM: But I think your art is bigger than that, that although it includes these concepts, these anxieties, it alludes to something that goes way beyond ecological concerns. I think it deals with deeper issues. It discusses, in a very encompassing way, the issue of life and death. And it creates a very strong link between culture and nature, between human life and its connection to the natural environment. There are a lot of people fighting for ecology, and you are one of them, but at the same time you create a work that surpasses this discourse. Your poetry reaches other levels and other spheres of the human being, bringing perplexity of the destructive power, the perversity of our society. That is what touches me in this work of yours. JP: That is true, what really makes me move is not a purely ecological discourse. The issue for me is that right now we need to create signs that somehow allow us to interrupt this collective hypnosis. We need to wake up and shudder. FM: Frans Krajcberg has been dealing with that in an intense and incisive way. And he operates with aesthetic elements from the modernity. But this work of yours has greater impact, is more aggressive. Krajcberg turns to nature in itself, dramatizing this issue; while you turn to nature from a human perspective; your tree discusses our culture, our eschatology, our life and our death. And that is why this work had such an impact on me. ________________________________________________________________ Notes (1) Javier Clavo (Madri, 1918-1994) was a Spanish painter and sculptor, whose initial works depicted imaginary machines. He also designed cinema sets. In 1951, he traveled to Italy, where he studied fresco and mosaic techniques. In the 1970s he was a member of the Estampa Popular group, and at that time his work became realistic and full of social criticism. His style shows Cubism and Expressionism influences. His paintings often show great chromatic violence. (2) Álvaro Apocalypse (Ouro Fino, Minas Gerais, 1937- Belo Horizonte, 2003) is one of the best known plastic artists from the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. His artistic career began in 1957, with publicity illustrations, and he later dedicated himself to the plastic arts. His first exhibition was at the Atrium gallery, in São Paulo, in 1964. He was a painter, draftsman and scenographer. He also created marionettes, and in 1970 he cofounded the Giramundo puppet theater with Terezinha Veloso and Maria do Carmo Martins. Giramundo was very active in Brazil, and became internationally renowned. (3) Rubem Valentim (Salvador, Bahia, 1922 – São Paulo, 1991) was a self-taught artist who started painting in the 1940s. At that time, along with other then young artists such as Mário Cravo Jr., he contributed to the movement of renovation of the Bahia cultural scene. He graduated as a dentist in 1948, but slowly drifted away from this profession to dedicate himself completely to painting. Later he also studied journalism, graduating in 1953. His work gradually incorporated elements of African religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda, which are present in the form of signs and emblems, allying the use of geometry to that of intense colors, giving it a unique and creative content. (4) Ronaldo Rego is a relatively unknown artist. He was born in 1935, in the Brazilian state of Bahia, and his work was only exhibited a few times. In 1988 he participated in a major international exhibition, “Magiciens de la Terre”, organized by the Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris. Although white, Ronaldo Rego is deeply involved in Afro-Brazilian themes, including elements of the Umbanda cult. |

|||